Monthly Archives: August 2019

An abecedary of Sacred springs of the world: Spring of Giving Life of Istanbul, Turkey

“O Lady graced by God,

you reward me by letting gush forth, beyond reason,

the ever-flowing waters of your grace from your perpetual Spring.

I entreat you, who bore the Logos, in a manner beyond comprehension,

to refresh me in your grace that I may cry out,

“Hail redemptive waters.”

The ancient city of Istanbul is a melting pot of religions and cultures. As a result it is an excellent place to search for holy wells. The most famous is the Life Giving spring or font or Hagiasma which survives despite a history of destruction revealed to a Byzantine soldier called Leo Marcellus who became the Emperor Leo 1 who reigned between AD 457-474.

The Hagiasma By Alessandro57 – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11878406

The legend according to Nikephoros Kallistos Xanthopoulos a Greek Historian writing in 1320 occurred on April 4th 450. At the time outside the Porta Aurea of the city of Constantinople there was an overgrown grove of trees where a shrine with a polluted spring existed. It is described that as Leo was passing a grove of trees, he passed a blind man who was lost. Leo helped him find the path and seated him in the shade. The blind man was thirsty and so Leo looked for some water. In his search, Leo heard a voice say

“Do not trouble yourself, Leo, to look for water elsewhere, it is right here!”

However,he looked around and could see any. Then he heard the voice again

““Leo, Emperor, go into the grove, take the water which you will find and give it to the thirsty man. Then take the mud and put it on the blind man’s eyes. And build a temple here … that all who come here will find answers to their petitions.”

Rather surprised by the voice he did as told and once mud was placed on the blind man’s eyes and he miraculously regained his site. Finally when Leo became Emperor he built a church on the site of the spring.

After his accession to the throne, the Emperor erected a church to Theotokos or St Mary. The spring continued to provide healing waters and in particular was said to allow people to be brought back from the dead hence its name. Indeed, the name Life giving font’ became an epithet for St Mary It became a major pilgrimage site in the Greek Orthodox church who celebrate the spring on Bright Friday in the Orthodox church. .

The present church is also rectangular and the spring arises in a crypt outside the church adorned with icons and paintings surmounted by a dome painted with an image of Christ in a starry sky. It is accessed a stairway parallel to the longer side of the church. The springs water flows into a marble basin. Inside the basin can be seen fishes who have been present in the water for several centuries. This is remembered in the complex’s Turkish name balikli the “place where there are fishes.

How did the fish end up in the holy well? It is said that a monk was frying fishes in a pan nea the shrine when a fellow monk told him of the conquest of the city by the Ottomans. He did not believe the other monk saying he would only believe it if the fish he were frying came back to life. At that point they did, jumped from the pan and into the water and began swimming!

Joseph the Hymnographer in the 9th century wrote a hymn to St Mary called Zoodochos Pege:

As a life-giving fount, thou didst conceive the Dew that is transcendent in essence,

O Virgin Maid, and thou hast welled forth for our sakes the nectar of joy eternal,

which doth pour forth from thy fount with the water that springeth up

unto everlasting life in unending and mighty streams;

wherein, taking delight, we all cry out:

Rejoice, O thou Spring of life for all men.

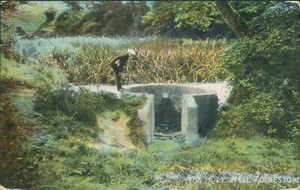

In search of the healing and ancient wells and springs of Folkestone part one – The holy well

The seaside Kent town of Folkestone has three notable water sites The first is perhaps the commonest picture postcard available and there are several versions as can be seen here. This is surprising as the site is not particularly well known or celebrated. Indeed its’ provenance may be perhaps a little dubious. This is the Holy Well or St. Thomas’s Well (TR 221 382) is. Its first description by S. J. Mackie in their 1856 Handbook of Folkestone gives the greatest detail and describes the scene around the well:

“Whence we look down its sheep trodden sides into the deep dell, where, sheltered by the rank rushes lie the dark un-ruffled waters of Holy Well. Do these raise tracings on the grass cover the remains of some lonely hermitage. The Country people tell you something about the pilgrims to Becket’s Shrine, it is called also St. Thomas’s Well, resting here on their way to Canterbury.”

Watt (1917) in discussion of the town notes in Canterbury Pilgrims and their ways:

“..also on the hills above it we have St. Thomas’s Well, but such are scattered all over the district.”

Samuel J Mackie records in 1856 A description and historical account of Folkestone

“Sheltered by the rank rushes lie the dark waters of Holy Well Do those raised tracings in the grass cover the remains of some hermitage The country people tell you about the pilgrims to Becket’s shrine it is called St Thomas’s Well resting here on their way to Canterbury I confess it seems to me slightly out of road but there it is and all I can tell about it is there is nothing now to be told.”

In the 1865 an illustrated hand-book to Folkestone and its picturesque neighbourhood by H Stock

“A short distance from this to the immediately at the bottom of Sugar Loaf Hill a remarkable spring of beautiful water known as Well or St Thomas’s Well Why so called saith not By some it is thought that it was resting place of the pious souls who worshipped shrine at Canterbury but how those worthies here cannot be conjectured It is now used as sheepwash”.

This latter point would explain the odd concrete structure, now lost, seen in some postcards.

In the 1925 Wonderful Britain by John Alexander Hammerton he noted:

“Folkestone’s Holy Well, sometimes called St. Thomas’s well…the old highway to Canterbury runs close by and tradition says that pilgrims to the shrine of St Thomas a Becket used to drink here and that Henry II himself did so when he went to do penance at the Cathedral whose Archbishop he had murdered and martyred.”

When visiting in the 1990s the information board states that the name holy well is a modern name for these springs, and 80 years ago one was called St. Thomas’s Well but the account above disagrees. There appears to be some confusion over the site. Consequently it is difficult to pinpoint the exact site. I was informed by a local in his late 60s that, when he was a boy, the second now dry spring was called Holy Well. The spring arose in a deep gully, now covered with bramble and heavily eroded at the source. However, continuing the path around to the base of the hill, one comes across a large pool, fed by all the springs. This is the site called the Holy Well on an early 1900s postcard. So perhaps there were two sites after all?

When William Parsons of the excellent British Pilgrimage Trust visited the site was largely overgrown and derelict as can be seen here in 2016, he repairing it with some stones found around which may have been part of the original structure.

Next time we shall be exploring Folkestone’s attempt to develop a spa.

The sacred landscape of Ilam Staffordshire – the Holy Well of St Bertram, his shrine and cave

Just a small distance from the highly visited Dovedale is a sacred landscape of hermitage, holy well and shrine. Ilam boasts a rarity in England a largely intact shrine with its foramina (holes in which the pilgrim could insert ailing limbs and get closer to the holy person). The shrine is that of Beorhthelm or Bertelin, Bettelin or more commonly Bertram. The patron saint of the county town of Staffordshire, Stafford.

Who was Bertram?

Bertram is an interesting local saint, dating from around the 7th-8th century in what was the Mercia. Briefly, he is said to be of Royal Irish lineage but after making a princess pregnant, escaped to England where he sheltered in the woods around Ilam. The story is told by Alexander, a monk, in the 13th century who notes:

“They were in hiding in a dense forest when lo ! the time of her childbirth came upon them suddenly ; born of pain and river of sorrow! A pitiful child bed indeed! While Bertellinus went out to get the necessary help of a midwife the woman and her child breathed their last amid the fangs of wolves. Bertellinus on his return imagined that this calamity had befallen because of his own sin, and spent three days in mourning rites”.

As a result he became a hermit living in a cave in the valley near Ilam. Despite the earliest mention being Plot, the local geography is suggestive that this is the site of an early Christian hermitage site, although no mention of a well is noted in his legends it can be noted. The cave itself still exists but reaching it appears to be problematic. Only being accessible when the river Manifold dries which suggests a very useful hermitage site. However, it is worth noting that some accounts have the cave being Thor’s cave further up. Perhaps this is significant as it suggests a Christianisation of a pagan site.

Two wells?

One well up on the hillside has perhaps the greatest provena is surrounded on four sides by varying low stone walling, about two feet or so at its highest (although it appears to have been built up and down over the time I have visited the well). The spring flows from a small, less than a foot square chamber, enclosed in stone and set into the bank through a channel in the rubble flow and out along the path towards it.

Since the 1990s, on the first Saturday in August, the Orthodox Church makes a pilgrimage to the site and blesses the well.

Interestingly, literature available from the National Trust shop fails to mention this well, but notes a more substantial second St Bertram’s Well. This is close by the church and surrounded by a rectangular stone wall with steps down, the water arises here at greater speed and flows into the nearby River Manifold. Visually it is more impressive and more accessible but whether there is any long tradition of this second well is unclear, but authors such as the Thompsons’s (2004) The Water of Life: Springs and Wells of Mainland Britain and Bord (2008) Holy Wells of Britain appear to have fostered its reputation.

Little is recorded of the wells, but Browne (1888) in his An Account of the Three Ancient Cross Shafts, the Font, and St Bertram’s Shrine, at Ilam, noted that the ash had gone, but the water was still being used. He states that:

“The late Mrs Watts Russell always had her drinking water from it.”

Since the 1990s, on the first Saturday in August, the Orthodox Church makes a pilgrimage to the site and blesses the well. Interestingly, literature available from the

Sacred tree

More is recorded is rather curious. Plot (1686) in his The Natural History of Stafford-Shire, the earliest reference of this fascinating site and he records that a

“St Bertram’s Ash… grows over a spring which bears the name of the same Saint… The common people superstitiously believe, that tis very dangerous to break a bough from it: so great a care has St Bertram of his Ash to this very day. And yet they have not so much as a Legend amongst them, either of this Saint’s miracles, or what he was; onely that he was Founder of their Church”

Such ash trees are commonly associated with holy wells. It is worth noting that in North myth, the sacred Yggdrasil was an ash tree associated with divination and knowledge. In some places rags would be tied to such trees but no such record exists here. By the late 1800s as noted in A general collection of voyages and travels digested by a J. Pinkerton in 1808 that the:

“Ash tree growing over it which the country people used hold in great veneration and think it dangerous to break a bough from or his in the church which are mentioned by Plot I did not hear of it at the village.”

Thus suggesting by that time it had gone by this time

A final observation is that in the 1800s a Roman relic found there:

“In the parish of Ilam near the spring called St Bertram’s there was found an instrument of brass somewhat resembling only larger a lath hammer at the edge end but not so the other This Dr Plot has described in the XXIII Tab 6 This he takes to have been the head of a Roman Securis which the Papoe slew their sacrifices.”

Does this suggest that sacrifices were made at the spring by the Romans?